THE DRAG — WHERE CHANGE TOOK ROOT AND THE UNIVERSITY PUSHED BACK.

How protest turned the eyes of the nation to Austin, and how it literally changed the campus architecture.

Editorial Note: My wife and I sit in a season of change, her mother passing last Thursday and mine in the final stages of hospice. That’s blurred the boundary between what I’m feeling and what I’m covering. I do not wish to conflate legacies, but do wish to pay tribute to Elinor James Johansen and her lifelong commitment to social justice. I’m obliged for your indulgence. Alan Berg, Publisher.

History’s intersections fascinate me, how we’re shaped by events. Elinor Johansen came to the University of Texas to study sociology, and was a student in 1956 when UT admitted the first black undergraduates. The following year, the College of Fine Arts cast a black mezzo soprano, Barbara Smith, opposite a white male student as the female lead. All hell broke loose.

She began receiving threatening calls and was accosted on campus by an unknown man who spat in her face. Eventually, the uproar caught the attention of the Texas Legislature, where Smith’s own representative from east Texas, Joe N. Chapman, threatened cuts in the university’s appropriation if Smith were allowed to perform. Ultimately, UT President Logan Wilson decided to remove Smith from the role. Humanities Texas, 2011

Elinor spoke out against the decision. She’d found her first fight.

At the time, segregation was the norm in Austin—no dormitories, restaurants, or barbershops served African American students, and the Ku Klux Klan marched openly down Congress Avenue. Humanities Texas, 2011

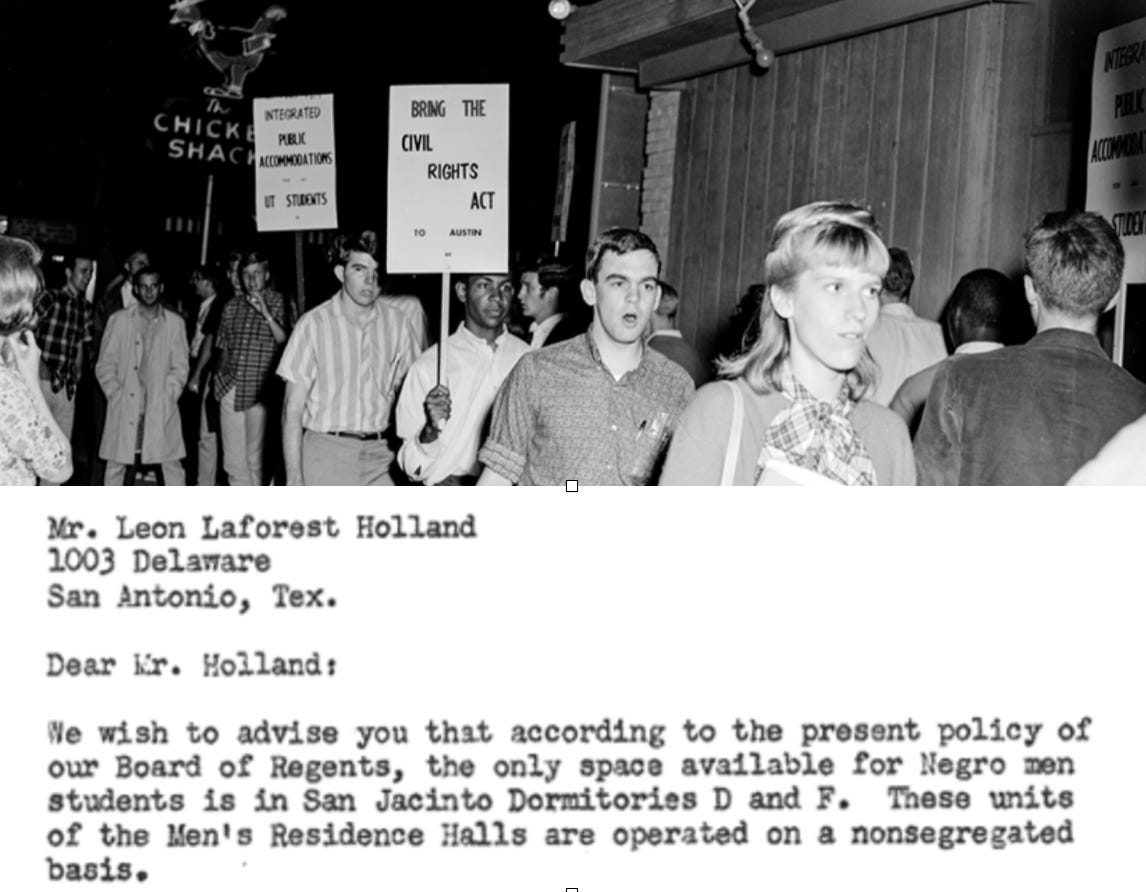

The protests on behalf of Smith were part of a growing civil rights movement, and in 1960 a group called Students for Direct Action, or SDA, set up shop just beyond the University’s reach, across Guadalupe at the YMCA on the Drag. UT History Corner lays out the story:

The group had initially been formed as the Human Relations Council, under the auspices of student government, but (co-founders) thought the University’s regulations that oversaw student activities would eventually thwart their efforts.

As SDA members discussed plans to persuade theaters along the Drag to integrate, African American student Houston Wade made a suggestion. A variation on the sit-in, Wade called it a “stand-in.” Persons would line up at the box office, and when their turn came to purchase a ticket, would politely ask, “Is this theater open to all Americans?” When told it was limited to white customers only, the person would return to the end of the line and repeat the process. This had the effect of both raising the issue and clogging up the line.

The gatherings grew and became something of a happening, complete with songs, chants, placards and cameras. Theater managers and business owners were flummoxed.

“I was the first to serve Negroes on the Drag … about three years ago,” one restaurant owner explained in the Texan, “and I got a violent reaction. A majority of my customers didn’t want it – they wrote letters, and protested in person – so I changed back.” A store manager said of the student demonstrators: “They haven’t grown up. None of them have had to make a living for themselves.”

Then the protests caught the eye of former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

It is interesting to note that it is the white students in many of the Southern universities who are really carrying the fight for integration. Students from the University of Texas, for instance, have set themselves the task of picketing the Austin theatres, which are not integrated, in an effort to bring before the public the fact that the city's theatres are segregated. I am personally grateful to the Texas students for making the effort to bring about the end of this kind of segregation in their state. But I wonder why students have to be without the help of the community in general. Eleanor Roosevelt, Dec 23 1960

Roosevelt’s comments brought more attention from the national press.

TIME magazine and The New Republic printed articles, and venerated television and radio journalist Edward P. Morgan delivered a sympathetic commentary to his listeners nationwide.

By summer’s end, the theater owners had capitulated. Within a year, most of the other shops along the Drag ended segregation as well.

*Here is a more detailed account from the UT History Corner, the source for much of the above.

A FOOTNOTE ABOUT BARBARA SMITH CONRAD

“I wanted to just say everything that came into my mind, but I was trying to be that person who was a healer. That was part of the upbringing. You tried to make peace and not war.” Barbara Smith Conrad

On January 31, 1959, Conrad earned her bachelor of music degree following a “successful recital in a packed auditorium that ended in a standing ovation.” After graduation she decamped for New York, where Conrad became a featured performer on some of the the most prestigious stages in the world.

In 1985 she was named a University of Texas Distinguished Alumna, and the Barbara Smith Conrad Endowed Presidential Scholarship in Fine Arts was established at her alma mater in 1986. She was awarded the Texas Medal of Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement and the History-Making Texan Award in 2011. In 2012 she was named an artist-in-residence and visiting professor to UT’s Butler School of Music. That same year she was inducted into the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame. Teresa Palomo Acosta, Texas State Historical Association.

A FOOTNOTE ABOUT ELINOR JOHANSEN

After receiving a doctorate in sociology, Elinor and husband Kjell moved to Denton. She joined the faculty at Texas Woman’s University and developed a reputation as the town contrarian (or as my dad put it “that communist”) through frequent letters to the editor. Her words still carry power, still carry her voice — fearless and opinionated, a fire stoked through a lifetime.

On the Confederacy

“One does not need to be black or have enslaved ancestors to be offended by the use of the Confederate battle flag outside of a museum or one of those asinine Civil War re-enactments. I am white and had ancestors who fought with the rebels, and I find the use of the flag as simply a way of annoying people, uncalled for, childish and just plain stupid.”

On the Texas Constitution

“Many years ago, and very young, I was working in a research museum in the north of Norway and found myself held responsible for the awfulness of the Texas Constitution. I had no idea what those people were talking about; I had yet to take my Texas government class at UT. I was informed by all the scientists that our Texas Constitution was known worldwide as the best example of how not to write one.

At the time, I figured that was an exageration. Later, after finishing college and moving to Denton (1964), I found myself voting on a state constitutional amendment that would allow an elderly couple in Tarrant County to keep their goat.

I voted for the goat.”

On Athiesm

“I think the mistake is in thinking (believing) that a person must have some sort of supernatural explanation in his or her life. Some of us just know that we do not know and don’t spend a lot of time worrying about it. It is possible to live without “belief” and not find it necessary to latch on to whatever the going god thing is at the moment.”

Elinor James Johansen, 7 February, 1933 – 10 October, 2024.

A FOOTNOTE ON THE DRAG: HOW PROTEST CHANGED THE ARCHITECTURE ACROSS THE STREET.

When this photo was taken, the West Mall—bounded by the Tower, the Union, the Drag, and Goldsmith Hall—was covered in grass, making it a popular gathering place for students. Protests held in front of the Union often turned the grass to dirt underfoot. According to previous Alcalde reporting, Board of Regents Chairman Frank Erwin didn’t like the look of these hippies, so he added concrete walkways and large azalea planters to control foot traffic and an “out-of-scale” fountain to limit visibility from the street.

The Daily Texan ran pages of scathing editorials about the project. “There is something tragic about destroying the present state of the earth on the West Mall, then spending a quarter of a million dollars to make it look modern,” an editor wrote in a 1973 summer issue. The installations would nevertheless be completed in 1975. Eliza Pillsbury, Alcade, Feb 2024

On we go.

Alan Berg, Publisher.

How are we doing? We want to hear from you.

Take this quick survey and help us make Happy Heat better.

Go see something, tell us about it, we’ll share more stories next week.

Let’s build something together. We’d be forever grateful for your help, and an easy way to do so is by subscribing to the Happy Heat Substack. What comes in goes right back out in artist commissions and live shows. To which you’ll get to come! For the first 100 subscribers, we are offering 20% off forever.